ICANN’s decision to redact WHOIS ownership information in view of GDPR requirements has significantly impacted the way M&A lawyers conduct due diligence on domain names. Here’s why, and some practical workarounds.

How has GDPR affected WHOIS searches?

The non-profit organisation ICANN coordinates the databases of general top-level domains (gTLD, for example .com or .net) and country-code domains (ccTLD, for example .uk or .eu). Individuals or corporate registrants can purchase rights to domain names through an ICANN-accredited registrar (for example, Domain.com and Nominet).

After the GDPR came into effect in 2018, ICANN published the Temporary Specification for gTLD Registration Data, a policy which requires registrars to heavily redact WHOIS search results to remove personal information. The Temporary Specification states in part that:

“In responses to domain name queries, Registrar and Registry Operator MUST treat the following Registrant fields as “redacted” unless the Registered Name Holder has provided Consent to publish the Registered Name Holder’s data:

- Registry Registrant ID

- Registrant Name

- Registrant Street

- Registrant City

- Registrant Postal Code

- Registrant Phone

- Registrant Fax”

The Temporary Specification also provides that WHOIS search results “MUST provide in the value section of the redacted field text substantially similar to the following: ‘REDACTED FOR PRIVACY’”.

Impact on M&A Transactions

The consequence of this policy is that it is now difficult for buyers (and their lawyers!) to confirm who “owns” domain names.

Purchase agreements will include intellectual property ownership warranties, and these will cover domain name registrations. However, while warranties offer strong protection for buyers, they are not a perfect solution. For example, a seller may mistakenly believe that it owns domain names when in fact it does not. This often happens when a company’s IT employees apply for the domain names as individuals. Things get tricky when these employees leave, and no one remembered to transfer the domain names back to the company.

Also, domain names are hard to value – the registration might only cost a few dollars, but it may host a valuable branded website. Therefore, even when a domain name warranty is breached, the buyer may not adequately be compensated.

Practical solutions

- Reverse WHOIS Lookup: A number of websites offer limited WHOIS results through a “reverse WHOIS lookup” search, which searches by owner rather than by domain name. While the completeness and reliability of this data is often uncertain, it at least provides a starting point.

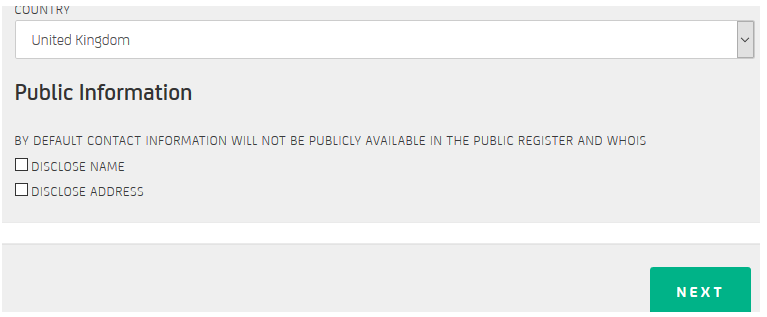

- Seller consent to publish records: ICANN has said that a domain name owner can consent to disclose its details, and so a seller may update these as part of the due diligence process. We have discussed this approach with several registrars: one ccTLD registrar explained that providing consent is a simple tick-box through their online portal (see below), while other registrars were less confident on their processes.

- Offline copies of records: The buyer may ask the seller to provide print-outs of its records showing that it is the current registrant of the domain names. While less reliable than WHOIS records, screenshots from the domain name registrar’s management portal may provide some comfort that the seller is the relevant owner.

- Joint review of the online records: To take the above approach one step further, the parties could negotiate limited and restricted login access for the buyer’s IT team (or a mutually agreed third party consultant) to jointly inspect the online records with the seller in real time to verify ownership, provided that the relevant registrar’s terms of service and any confidentiality restrictions are followed.

- Website indicators: The seller could change the content of the website in a way that has been pre-agreed to demonstrate ownership. For example, the seller could create an additional page and share its link with the buyer, taking care to include coding that prevents web crawlers from including this in their search results.

- Domain name assignments: In an asset purchase scenario, the domain name assignment (either alone, or wrapped into the omnibus IP assignment) can include language where the seller assigns, and agrees to procure the assignment of, the relevant domain names (to the extent not owned by the seller, and at the seller’s expense). This ensures that the seller has ongoing obligations to help transfer these domains post-closing, and can be coupled with more detailed further assurance clauses.

These options carry practical complexities and additional risks around accuracy, reliability and transaction confidentiality, but may go some way to providing additional comfort to buyers.